Malvertising on Google Ads: It's Hiding in Plain Site

Let’s start with a hypothetical: If I asked you to download a piece of open source software, what would you do? Chances are you’d open your browser, go to Google, and type in the name of the software.

Then you’d proceed to click on the first official-looking link you saw, even if it’s an ad. After all, it doesn’t really make a difference if you click on an ad or an organic link as long as you wind up on the site you’re looking for.

You won’t think too hard about clicking a Google ad because you have no reason to be suspicious of them–they’re just part of the background noise of your digital life. It’s the same reason you don’t check to make sure that gas, and not water, is coming out of the pump when you fill up your car.

But that assumption of safety is exactly what cybercriminals are counting on. It’s at the heart of the latest form of malvertising, in which bad actors purchase Google ads that sit at the top of search results and masquerade as legitimate open source software. But when you click the download button, what you’re getting is malware.

Open source software seems like a curious choice as an attack vector until you understand how much the technology has permeated corporations. In OpenLogic’s 2023 State of Open Source Report, 80% of those surveyed reported that their organization increased the use of open source software over the last 12 months.

With little mainstream news coverage, malvertising has evolved to become an extremely worrisome attack vector. And as open source software becomes more common in the business world, the threat is shifting from individuals to organizations. To protect not only your end-users, but your corporate fleet, IT and security folks need to start figuring out how to guard against this threat.

What Is Malvertising?

Malvertising is a broad term that encompasses any time bad actors use digital advertisements to deliver malware. Malicious advertising has taken many forms over the years–display ads, drive-by downloads, and forced redirects–with headline-worthy results affecting organizations from the New York Times to the NFL.

The goal of these past malvertising campaigns was to get users to inadvertently download ransomware. Some malvertising required a click; some didn’t; some took the form of urgent looking pop-ups; some looked like regular ads. Regardless, they all had the same effect: encrypting the user’s device until the ransom was paid.

However, all these variations can be seen as traditional malvertising, which peaked in the 2010s. In this article we’re going to focus on malvertising’s newest form, which has some unique characteristics. For one thing, in open source malvertising, users aren’t unknowingly downloading a file; they’re doing it on purpose. And paradoxically, that makes it more dangerous.

How open source malvertising works

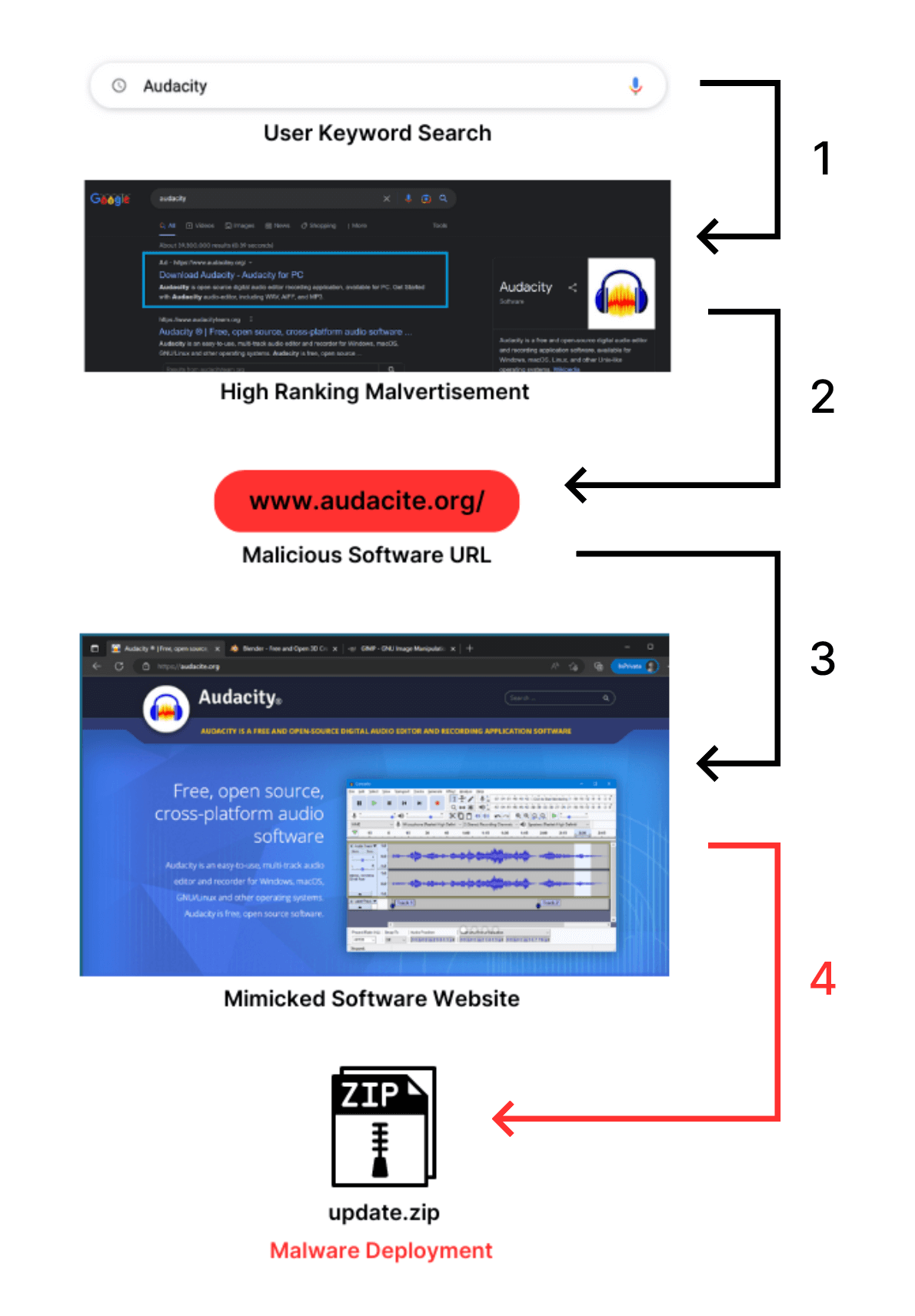

Victims of Google ad malware typically follow this flow:

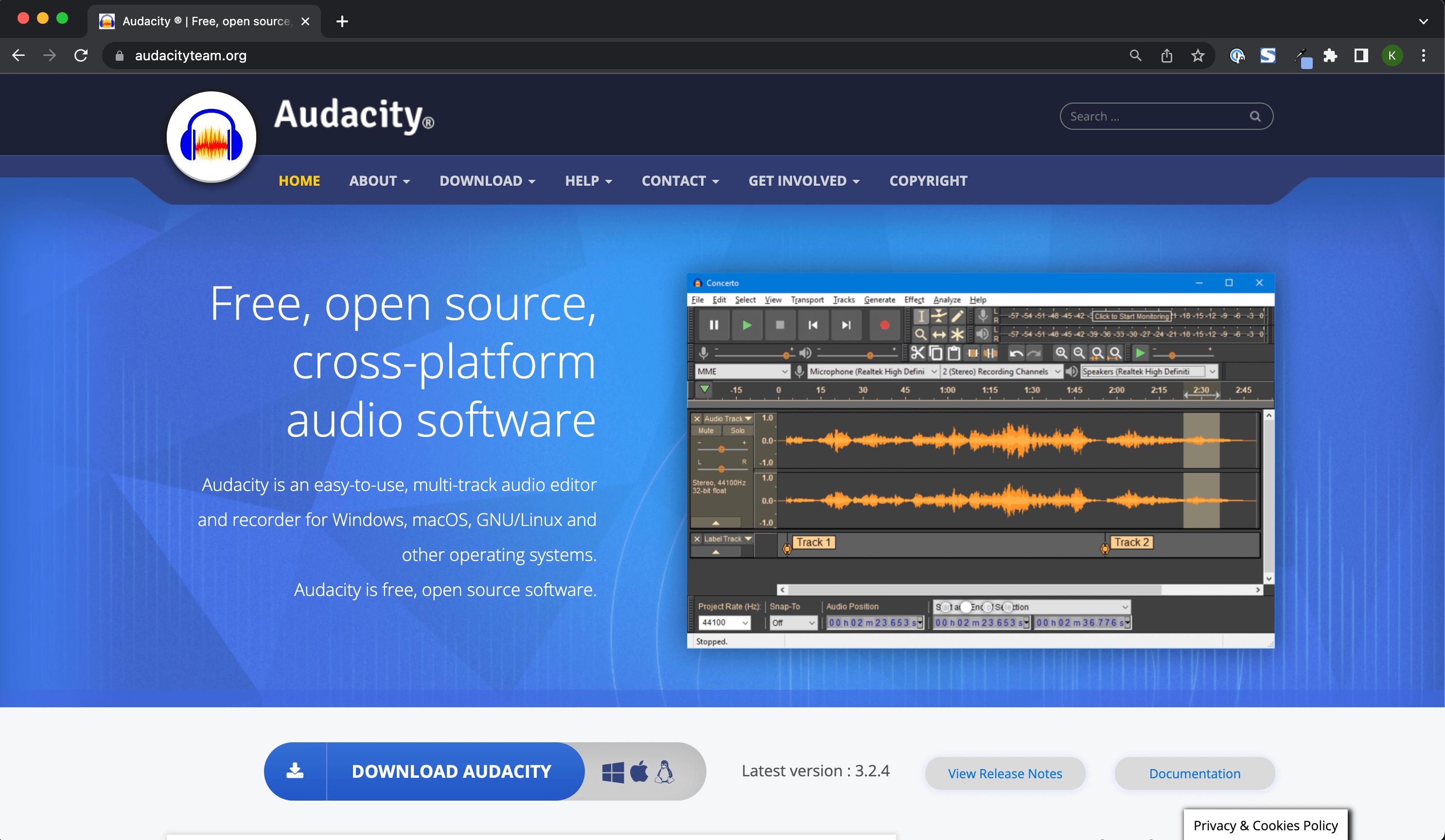

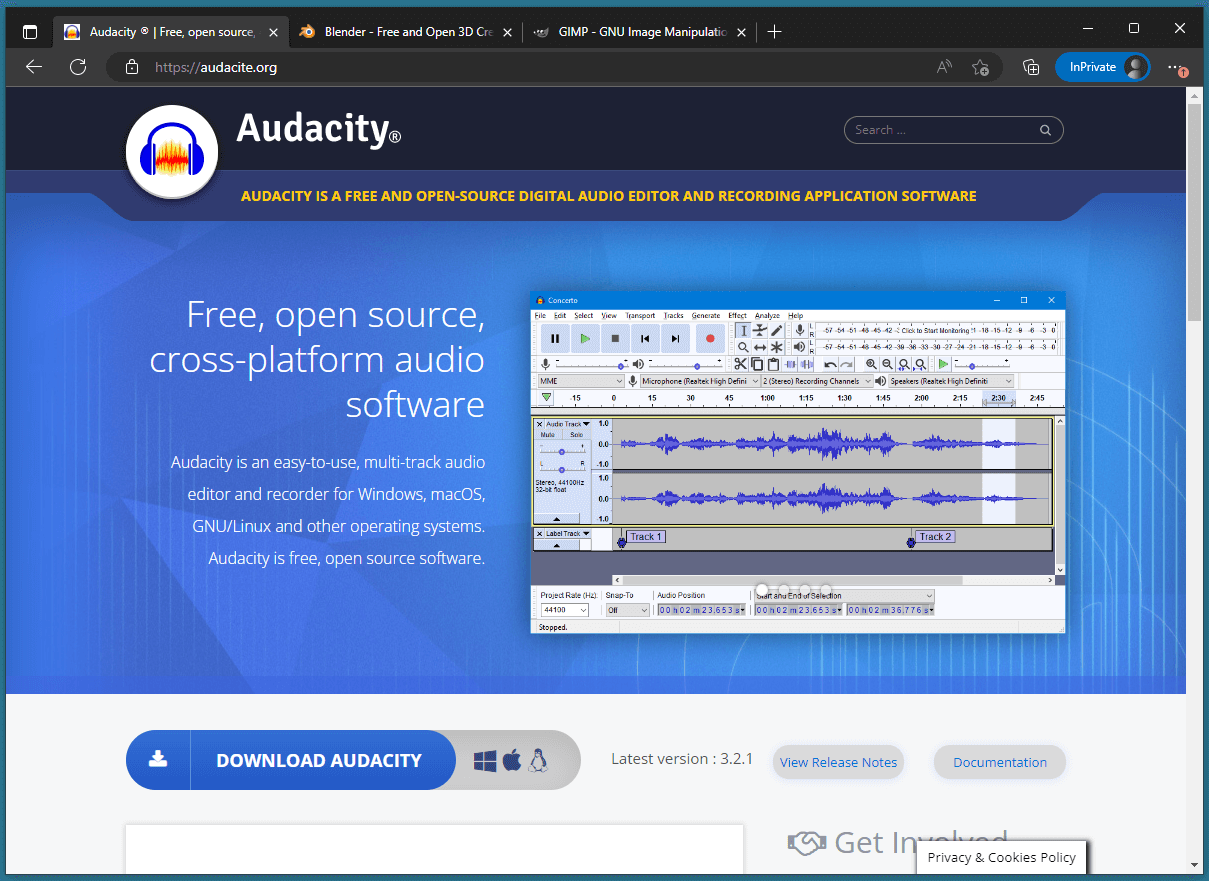

First, users see the promoted search result, which most likely features a typosquatted URL that’s easy to miss if you’re not paying close attention. (In the example below, “audacity” becomes “audacite.”) Next, they click on the URL that takes them to a web page that’s nearly identical to the real company’s homepage.

And that’s where the trouble begins. Once victims download the fake Audacity software they’re met with Vidar Stealer—an information-stealing malware capable of gathering passwords and information from two-factor authentication software.

When the user opens the downloaded file, they find a malware file named “update.zip” that is wrapped in a bloated file–343MB!– which mimics the size of a real installer to avoid initial suspicion from users and malware detectors.

Malvertising Examples

Search engine malvertisements have proliferated to such an extent that the FBI released a bulletin about it (among other things, they recommend individuals protect themselves by using ad blockers).

To become so notorious, Vidar Stealer can’t be the only malware distributed in these targeted attacks. Risky Business News has collected a comprehensive list of malware attached to Google Ad malvertising over the past year, including (get ready): IcedID, BatLoader, PrivateLoader, NullMixer, FakeCrack, RedLine Stealer, Rhadamanthys Stealer, Yellow Cockatoo, VagusRAT, and MasquerAds.

This generation of malware delivers many types of malicious code: credential stealing, remote access installation, ransomware, additional loaders, and even the ability to steal cryptocurrency.

Audacity isn’t the only open source tool being used in malvertisements. Bleeping Computer reports that tools such as Rufus, Notepad++, 7-Zip, Blender 3D, and others have been used as vehicles in this malware delivery method.

If you’re overwhelmed by all the possible permutations of this type of attack, I think I can speak for the threat actors—that’s the point.

Why Malvertising Is a Threat To Corporate Security

With the proliferation of search engine malvertising, end-users run the risk of their personal and work information being stolen any time they open up a browser. And it’s not because end-users are dumb. It’s not because you’re not doing your job as a security practitioner. And it’s certainly not because these bad actors are geniuses.

It’s because these malvertisements combine unexpected and tried-but-true tactics that have morphed into a malware snowball rushing down exploit mountain. Let’s break it down.

Malvertising is a surprisingly popular attack vector

Part of the reason malvertising is so effective as a delivery vector for malware is that it gets comparatively little attention compared to email.

In HP Wolf Security’s Q3 2022 Threat Insights Report, 69% of the malware campaigns they analyzed occurred through email, making it by far the most popular method.

However, taking the silver medal are web browser downloads at 18%. “In total, we found 92 typosquatted domains likely related to the IcedID campaign, indicating the growing popularity of this delivery mechanism among threat actors,” says HP malware analyst Patrick Schläpfer when his team analyzed a recent malvertising campaign affecting established software.

While email is efficient at targeting a specific business or individual, search engine malvertising has a broader scope that can affect many businesses in one deployment. As the Vidar Stealer malware exemplifies, hackers can steal information from users and find themselves with a treasure trove of both personal and business logins. They’ll be able to quickly deduce what company a user works for, crack 2FAs nearly effortlessly, and access your systems.

While not an example of malvertising, the LastPass data breach is a case study in how consumer-facing software can be used for corporate cybercrime. In this attack, a hacker accessed a senior DevOps engineer’s home computer through media player Plex, and used it to install a keylogging malware that was able to scrape the engineer’s credentials. The hacker could then access LastPass’ customer database and make off with the sensitive information of their users.

Malvertising is to evade traditional detection methods

As we mentioned earlier, one reason open source malware has been so successful is artificial inflation of file size.

“First, a larger file size is more likely for a software installer. Secondly, and more importantly, extremely large file sizes can be used to bypass the automatic scanning of some antivirus software.” -HP Threat Research Blog

So, not only are malware detection tools fooled, but most end-users won’t notice the difference until it’s too late. And even when the software they thought they were downloading fails to install, plenty of users will think it’s a harmless glitch or a problem with their computer.

Users aren’t trained to detect malvertising

In order to avoid falling for a malvertising scheme, users have to know what to look for. That requires being skeptical about websites, closely looking at URLs, and not simply trusting a link because it’s the first result on Google.

Users aren’t taught this, especially not at work. Phishing emails and social engineering attacks are well-covered in most corporate security trainings. But these courses usually skip over malvertising, since in the past it wasn’t aimed at businesses.

Malvertising is difficult to keep up with

Since malvertising isn’t new, you’d think it would be easy to alert your end-users of the mechanism. But when you have an ever-moving target, it becomes a game of cat and mouse.

IT teams and security practitioners would be hard-pressed to hunt down individual ads, since the ads on search engine result pages (SERPs) change often. So getting ahead of this problem isn’t even whack-a-mole–it’s more like whack-a-ghost.

Despite the difficulty of keeping track of all the search engine malvertisement campaigns, the cybersecurity community has taken it into their own hands to report on it. Security researchers such as Will Dormann, Germán Fernández, and MalwareHunterTeam have been especially diligent about sourcing and relaying Google ad malvertisements to the public. But as long as bad actors can buy a spot on Google, the security world will always be playing catch-up.

The rising popularity of free and open source software

As we’ve noted, more and more companies are adding open source software to their tech stacks. Companies have also taken to utilizing free or low-cost password managers such as Bitwarden and 1Password to protect their end-users’ credentials. And threat actors have taken notice.

A recent phishing campaign spoofed Bitwarden’s login page for users who clicked the wrong Google link. While this isn’t strictly malvertising–the goal was to trick users into giving away their credentials, not install malware–the technique is essentially the same. The Bitwarden community surfaced this convincing imitation of Bitwarden’s landing page, and many concluded that the only way to be safe is to add the real page to their bookmarks, and bypass Google altogether.

Companies know they are at a disadvantage and 41.97% of organizations already admit that maintaining security policies or compliance for open source software is their biggest challenge–and this there’s a chance tha malvertising could make some companies conclude that it’s just not worth the risk.

How To Protect Your Users From Malvertisements

Most articles related to search engine malvertising are geared toward end-users, not admins, so they offer basic tips about adopting a think-before-you-click mentality. However, in a business setting, you may want stronger safeguards.

To protect your endpoints from malvertisements, you must implement scalable, reliable, and secure practices. And that’s easier said than done, since, as the saying goes: users be downloadin’.

Nevertheless, here are some actionable steps you as an IT administrator and security practitioner can take to protect your end-users and business.

Create blocklists for commonly used malicious-TLDs

Preventing exposure to malicious websites is key to maintaining a safe fleet. Users have traditionally used ad blockers to prevent being exposed to Google ads; however, Google has announced an update to their extension manifest that will effectively make Chrome ad blockers obsolete as Chrome will now have the ability to severely limit extensions from making network request modifications. To prepare for that upcoming reality, the National Security Agency recommends using your existing network functions such as your firewall to allow DNS traffic through corporate servers only.

The NSA also recommends utilizing DNS to block malicious ad domains. While it may be a daunting task to compile a blocklist of top-level domains (TLDs), the key is to just start. Fortunately, IT teams can use regularly updated, reputable, and community-maintained blocklists to catch malware. And for max coverage, ensure domains such as .site, .tk, and recently, .top domains that have been featured in these malvertising attacks are part of your growing blocklist as well. Create a weekly or even monthly task of updating the blocklist and your team can stay ahead of the game.

Implement an application whitelisting process

Installing new software is usually a pretty solitary activity: you pick the software you want, you download it, you use it. Pretty simple. However, as we’ve learned, with malvertisements, that user flow needs a bit of an adjustment—a democratic one.

Take Santa, for example. A binary authorization system for macOS, Santa allows organizations to monitor install executions and alerts users if a binary is malicious. If a user wants to install an unknown binary, they must apply for it to be whitelisted internally. However, tasking your IT team to look over each execution can be inefficient and arduous. Enter “social voting.”

The now-defunct Upvote, also a binary whitelisting solution, allowed organizations to create an application control policy server where users vote on and share software they’re trying to run. Once a certain threshold is reached, the software in question gets whitelisted and approved. Although the open source project is no longer being actively worked on, security teams can take the existing code and iterate on it based on their company’s needs. You can also find a similar social voting system to use in tandem with a process like Santa.

Create/update end-user security training

Let’s face it. Annual cybersecurity trainings are traditionally an hour-long chore that end-users only half pay attention to. They watch the videos, fill out three question quizzes per module, and the course tells them they “passed.” And usually, these trainings are outdated or repeating the same phishing stories.

To break out of this model and get your team’s attention, find time during the next all hands, team meeting, or catch-up call to talk about malvertising. Since malvertising affects all end-users, it’d behoove your organization to be proactive.

Show your colleagues examples of what malvertising looks like, explain what steps the organization is taking to mitigate exposure, provide tips on what they can do to protect themselves on their personal devices, what they can do if they think they’ve been infected, and of course, share this blog with them.

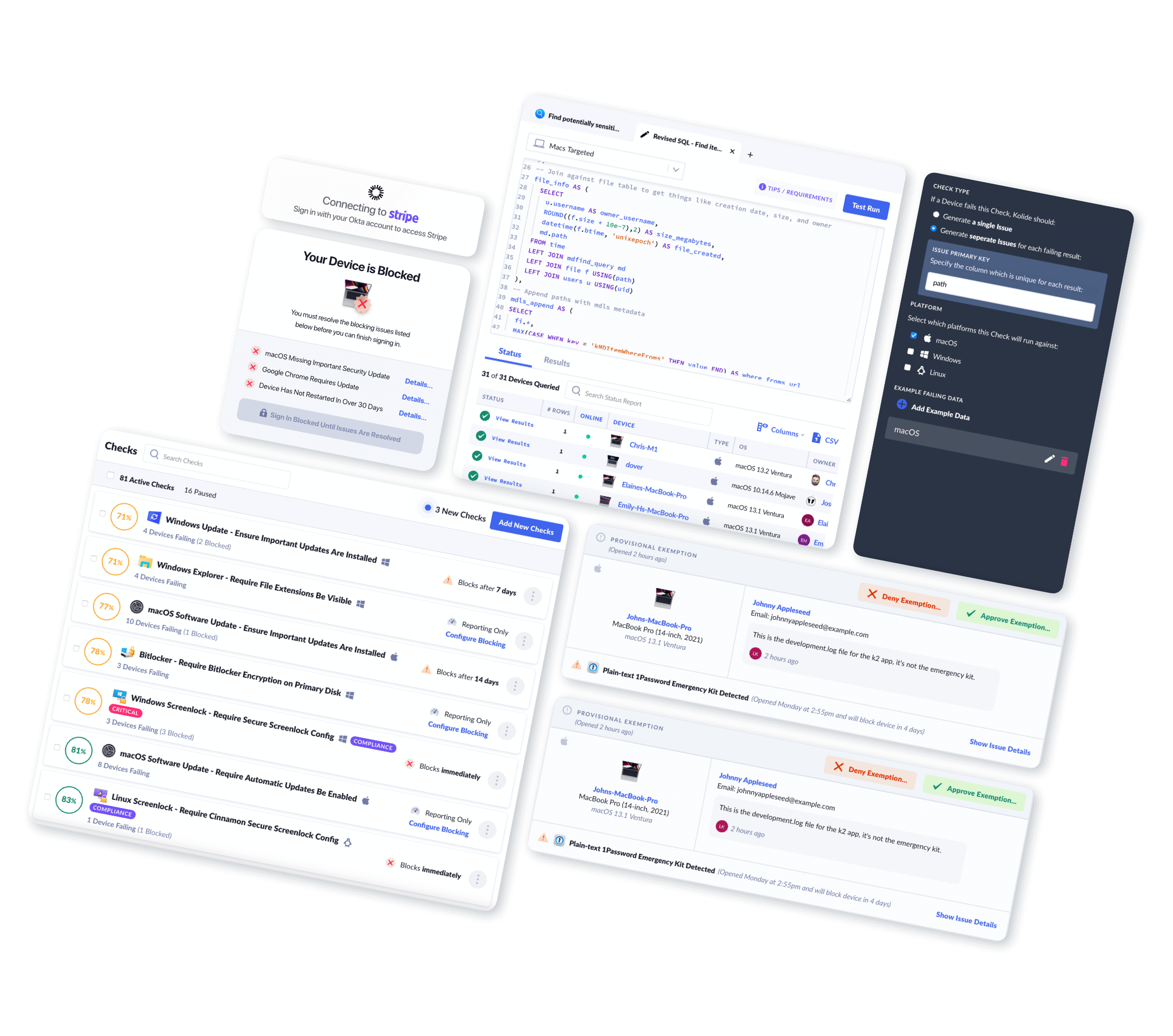

Create a Kolide Check

After we initially published this blog, one of our very own customers, Chainguard, mentioned that they had a close encounter with malvertising and used Kolide to mitigate some of the risk associated with it.

To protect themselves from malvertising, they wrote an osquery query that alerts them any time a .dmg, .iso, or .pkg file is downloaded from an unknown source, and deployed the query through Kolide. As they noted: “This query should not be your only line of defense, but can provide an early heads up before the package is opened.”

Kolide customers can run this query or use our Custom Check editor to write their own.

What is Google Doing About it?

We’ve talked about how IT teams and end-users can protect themselves from malvertising, but let’s be real: a lot of responsibility for this epidemic belongs to Google.

Google knows they have a problem and that their advertising network can be abused. Their 2021 Ads Safety Report says as much, as they:

Removed over 3.4 billion ads, restricted over 5.7 billion ads and suspended over 5.6 million advertiser accounts

Blocked or restricted ads from serving on 1.7 billion publisher pages

Took broader site-level enforcement action on approximately 63,000 publisher sites

Yet even with millions of advertiser accounts suspended, the problem isn’t going away. And as bad as malvertising is for users, it’s even more alarming to the businesses being mimicked, since they risk being branded as “unsafe.” Some of these companies are actively pleading for Google to do something.

Here are a few tweets about the issue:

1Password alerting followers that there’s impersonations going around.

Bitwarden calling out search engines for being the location of malicious links.

Open source broadcast software OBS relaying to users that they do not run Google ads and directing them to know what scams look like.

Open source multimedia tool VideoLAN explicitly stating how much trouble they’re having with Google taking down the malicious ads.

You can certainly sense VideoLAN’s frustration when they ask Google “how are those things a grey area?!?” The answer can be found in Google’s advertising policies, which seem to prioritize advertiser experience (and revenue) over user safety.

Google: “We have robust policies prohibiting ads that attempt to circumvent our enforcement by disguising the advertiser’s identity and impersonating other brands, and we enforce them vigorously.”

— Will Dormann (@wdormann) January 20, 2023

The real world: This is completely out of control and we can’t do anything about it pic.twitter.com/NYS7Il5MDx

Google classifies four things as “abusing the ad network:”

- Malicious or unwanted software

- Unfair advantage

- Evasive ad content

- Circumventing systems

From the list, malvertising falls directly into two categories: malicious software and evasive ad content, which is described as “manipulation of ad components (text, image, videos, domain, or subdomains) in an attempt to bypass detection and / or enforcement action.” With those boxes ticked, malvertisers are in clear violation of Google policy. So what’s the punishment? Per Google:

Violations of this policy will not lead to immediate account suspension without prior warning. A warning will be issued, at least 7 days, prior to any suspension of your account.

Sure, mistakes happen. Sure, your website could be hacked and injected with malicious content. But these threat actors are actively mimicking popular websites, exploiting the loopholes of the ad network, and reaping the reward–including a 7 day grace period. You’d think to yourself: there has to be a safeguard for extreme violators, right? You’d be correct – sort of. Per Google:

If we detect an egregious violation your account will be suspended immediately and without prior warning. An egregious violation of the Google Ads policies is a violation so serious that it is unlawful or poses significant harm to our users or our digital advertising ecosystem. Egregious violations often reflect that the advertiser’s overall business does not adhere to Google Ads policies or that one violation is so severe that we cannot risk future exposure to our users.

Unfortunately, the search engine does not provide a definition nor examples of what falls under “egregious violations.” And given how easy it is for bad actors to simply make a new account when a new one is shut down, this approach doesn’t meet the requirements for reliability or scalability. Still, when you look at things from Google’s perspective, these policies make sense.

In Q4 of 2022, Google search advertising accounted for $42.6 billion in revenue. There’s an understandable reluctance to put restrictive policies on a revenue stream as lucrative as ads are. So, until there’s a bigger outcry that forces Google’s hand, they’ll probably continue to respond to one business complaint at a time, instead of the issue as a whole.

If You Educate Them, They Will Avoid It

The war against malware is neverending, and the solution is not to lock down every device so users can’t download anything. (That approach will just drive them to shadow IT.)

What you can do is guard against known malicious software, make sure every employee’s malware blockers are up-to-date and running, and that employees aren’t accessing company resources on vulnerable, personal devices. And conveniently, you can do all that with Kolide! (You knew I had to plug the product in at some point.)

Finally, whether you use Kolide or not, don’t neglect the important role of end-user education. In the end, the easiest vulnerability to patch here might be ignorance. Because your end-users will continue to use Google every day. It’s about as inevitable as the search engine stating it has “put in place new certification policies and advertiser verification policies to better detect malvertising scams.”

Education and detection can prevent one bad click from turning into a security nightmare. All you need is the right mindset and the right tools. (Just double-check you’re downloading them from the right source.)

Want to see how Kolide can get your entire fleet updated, patched and compliant? Watch Kolide’s on-demand demo today.